[word count, minimal ~ 6,300]

[word count with all sections expanded ~ 13,000]

Why the selfie? Because there’s a part of the brain that works a bit like your camera app: it lets you focus (your attention) on the real world, or you can flip it and take selfies. I’ll let you guess what we do with it most of the time.

Over the last few decades, I have been writing to psychology and cognitive neuroscience researchers, hoping to find agreement on both the potential of the theory following, and on the urgency of research. However, I eventually faced reality. Despite the pleasures of cognitive decline, I am now in 3rd year BSc Psychology at Edinburgh University, with the ultimate aim, inshallah, of undertaking at least some part of the research myself.

It has frequently been argued that all behaviour, even the most seemingly selfless, can be explained by self-gratifying motives, but this is not the scepticism of the scientific method, it is dogma, armchair scepticism that could not survive a single interview with one of the surgeons in Medicins Sans Frontiers or MedGlobal who put their lives on the line and push the limits of endurance to operate around the clock in the hell of Gaza’s remaining emergency operating theatres. Over 1,000 health workers have been killed since October 2023.

A minority of psychologists such as Daniel Batson, have argued, without much success, that altruism is a very real driver of human behaviour. However, I have no reputation to lose. I can go much further. I will argue here that altruism is not only a commonplace driver of human behaviour, but that the concept of an egoism/altruism spectrum is crucial to understanding some of the most serious issues of our time, up to and including genocide.

In the following section, I introduce the idea of an egoism/altruism motivational spectrum and explain why I think research into this model of motivation has such far reaching potential. If you have time, please read this. [word count ~ 3540]

I once listened to a lecture by a philosopher who observed that, to a society of cannibals, the business of eating human flesh would be unremarkable. We live in a period which will be looked upon by historians as almost inexplicably barbaric. In July 2024, we elected the government that will dictate British foreign policy for the next five years, and yet only a small percentage voted in protest of the UK’s military and political support for the genocide in Gaza.

Our career politicians parrot ‘Israel’s right to defend itself’ as if the genocidal slaughter of an occupied people should be considered an act of self-defence. The stated goal was the elimination of Hamas. To kill a single Hamas commander in Jabalia, Israel dropped a 1,000-pound bomb on an apartment building murdering over 100 civilian residents. And this is only a snapshot of an ongoing daily catalogue of death and destruction inflicted on a trapped civilian population by a handful of war criminals at the head of a racist state armed to the teeth and granted unqualified impunity by Western politicians.

We rightly see it as manifest evil, but that term, however apt, shuts the door on understanding. Another perspective, as Tony Blair once explained, is that “someone has to be strong enough to take the hard decisions”. Adolf Eichmann would have supported this view. Like Nazis, both Joe Biden and Keir Starmer managed to rationalise the collective punishment of a population of two million, and the genocidal slaughter of sixty two thousand innocent civilians, including a confirmed minimum of twenty thousand murdered children, forty thousand orphaned children and an even greater number with lifelong disabilities. The human brain is absolutely incapable of processing the monstrosity of that reality, but Biden and Starmer have earned their place in history.

We have long since passed the stage at which alternative explanations might be argued. There is something seriously amiss with the mind of any individual who can tolerate what we have seen inflicted upon the people of Palestine, but to provide military support and political cover evidences a level of criminality that, it can only be hoped, will ultimately lead to the Hague.

However, Psychology is yet to arrive at the point at which it can identify the pathology common to these politicians and their fascist forebears. And there, I believe, lies the urgency of this research. I will argue here that this pathology can and must be researched. If the theory that I’m about to set out is sound, the pathology common to these politicians is closely related to narcissism. It is also dimensional, affecting a large proportion of the population, and it takes the form of an impaired development of the mechanism of baseline motivation. I will further argue that while the pathology itself must be understood in psychological terms, it is fed by and reproduced by the toxicity of our capitalist consumer culture. From the perspective of the victims of our elected governments, we are far, far worse than a society of cannibals.

narcissism: the natural motivational state of the infant personality

The theory rests on a model for the mechanism of baseline motivation which, if I am right, leads us to conclude that, in the infant personality, egoistic motivation is a thoroughly natural and healthy motivational state. Importantly, as I have said, this is not only a pathology of the individual, it is a pathology of Western culture.

The cultural discussion goes back to the 19th century when Auguste Comte called for a shift in French culture from individualism to cooperation and community: “vivre pour autrui.” But Comte’s concept of what came to be known as ‘altruism’ has little currency in modern science. Neither the motivational spectrum of altruism-egoism nor its far-reaching implications are yet recognised in Psychology.

Words often convey unintended meaning. Altruism, in this context, has nothing to do with being a nice person or performing good works. In this neurological context, it is a far more powerful driver of human behaviour. A by-product of the theory is the proposition that altruism and egoism are liable to be more or less normally distributed in any society, and that a slight shift in a society’s culture towards either extreme can have profound effects on the political behaviour of the nation.

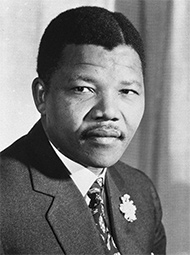

Our current understanding of altruism can be summed up in one word: surmise. It has been argued that we cannot categorically infer altruistic motivation from even the most selfless behaviour. However, the goal is to move from the story to the data. Let me begin with my conclusions. Egoism and altruism are emergent properties, manifestations of the primitive mechanism of baseline motivation, and a measure of both egoistic and altruistic motivation invariably co-exist in the normal personality. Some might lean more to one than the other, but it is a spectrum. This perspective allows us to consider the extremes of an imagined frequency distribution, and to visualise it in terms of the defining features of two very familiar personalities: the narcissism of Donald Trump, and the altruism of Nelson Mandela.

But here we have a problem. Psychology is comfortable with only the left side of this distribution. Narcissism is listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM5) as a personality disorder, not part of a spectrum extending to its logical opposite extreme. The profound and ubiquitous influence of altruism in behaviour is not recognised at all, and a disturbing number of psychologists argue that there is no such thing.

We might pull back from the extremes of Trump and Mandela, and consider the case in 2006 of nine ‘ordinary’ people who risked lengthy jail sentences for trashing the Raytheon arms factory offices in Belfast. This is just a quote from an old indymedia article but I think it might help bring some perspective to this zombie question of the non-existence of altruism:

After their acquittal on three charges of criminal damage to the computer equipment and office of Raytheon, the world’s largest supplier of guided bomb units, Colm Bryce and Eamonn McCann spoke to supporters and press outside the court. Colm Bryce began:

“The Raytheon 9 have been aquitted today in Belfast for their action in decommissioning the Raytheon offices in Derry in August 2006. The prosecution could produce not a shred of evidence to counter our case that we had acted to prevent the commission of war crimes during the Lebanon war by the Israeli armed forces using weapons supplied by Raytheon. We remain proud of the action we took and only wish that we could have done more to disrupt the ‘kill chain’ that Raytheon controls.

“This victory is welcome, for ourselves and our families, but we wish to dedicate it to the Shaloub and Hasheem families of Qana in Lebanon, who lost 28 of their closest relatives on the 30 July 2006 due to a Raytheon ‘bunker buster’ bomb. Their unimaginable loss was foremost in our minds when we took the action we did on 9 August, and the injustice that they and the many thousands of victims of war crimes in Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq and Afghanistan have suffered, will spur us on to continue to campaign against war and the arms trade that profits from it. We said from the beginning that we came to this court not as the accused but as the accusers of Raytheon.”

You might think their action was self-serving in that they will restore their self-respect, having done ‘something‘. Perhaps that is true, at least to some extent, but then there is Occam’s Razor. These activists had already done far more than enough to absolve themselves of the guilt of knowing and yet failing to act. They had tried everything to persuade their councillors and MPs that Raytheon was profiting from war crimes. They wrote letters, organised petitions, organised countless demonstrations and pickets, presented their research to politicians. Every attempt led to inaction on the part of the politicians. Eventually, they had exhausted every avenue, and in full consciousness of the probable consequences, they opted for the direct action which ultimately succeeded in expelling Raytheon from Belfast. And their motivation? The Shaloub and Hasheem families of Qana: “their unimaginable loss was foremost in our minds when we took the action we did on 9 August.”

Altruism has nothing to do with aspiring to become Mother Theresa, it is the predominant motivation of the mature adult personality. And, to be brutally frank, a lack of personal experience of one’s own atruistic (and egoistic) behaviour is something that might be expected of only the very young and life inexperienced. Any argument against the existence of altruistic motivation, however much it might masquerade as scientific scepticism, could only come from individuals who themselves still have some distance to travel to reach maturity. I’m afraid it has to be said. The time has come to move beyond the ‘question’. A strong enough case has not been made to argue against the immense potential of research into the mechanics of an egoism-altruism spectrum. Unless I am profoundly mistaken, altruism and egoism, as manifestations of baseline motivation, exercise a continual and profound influence on all human behaviour. If the model is sound, the mechanism of baseline motivation explains the actions of humanity at its best, and — all too familiar to us all now — humanity at its worst.

the role of commitment

The web is awash with articles teaching people how to increase their motivation, and I have yet to find one ‘expert’ who has grasped the utter simplicity of the role of commitment. As demonstrated by the Raytheon 9, and on the other hand, as any failing marriage can remind us, commitment is not binary, it is a matter of degree. And it is the degree of an individual’s personal commitment to the welfare of their spouse, their children or, like Mandela, his people, that determines the level of their altruistic baseline motivation. The ‘terrorist’, Nelson Mandela was an exemplar of committed altruistic motivation in the struggle for racial equality — and let us not forget as we read this that he was on the US terrorist list until 2008. The final paragraph of his statement addressing the court in the Rivonia Trial helped raise his profile to mythical status on the international stage. Here are Mandela’s own words:

The extremes of the spectrum help reveal the dimensional nature of egoism-altruism. Mandela and other ANC ‘terrorists’, are distinguished from the rest of humanity not by their altruism – for that is a motivation that we all possess – but by its degree: they were willing to give their lives. They were completely committed to the welfare of some ‘others’. Mandela’s raison d’être was to achieve the ideal of justice, and again, not justice for himself but for his people. Altruism is nothing more and nothing less than the commitment and thus the motivation to act for the benefit of someone other than oneself. When a parent gets up at three o’clock in the morning to attend to a child, that is altruism. It does not call for the courage of Mandela but it is altruism: motivation to act for the benefit of another. What is at issue here is simply the nature of baseline motivation and its relevance for Western culture.

A galaxy of pro-social or anti-social behaviours might be shown to derive from socially constructed norms. However, that is far from providing a complete picture. Egoism and altruism, as vectors of baseline motivation, operate at a profound level to influence individual life choices, and importantly, to influence the time and energy that an individual will invest in these choices. And most importantly, individual levels of commitment to the welfare of others are not fixed; they are fluid; they can change, radically.

I will take Palestine as an example. It is the most extreme case of racialised inequality in the world: half of the population under the control of the Israeli government has the right to self-determination, to security and to life, while the other half, because it is not considered to be of the same ‘race’, has the right to none of these. Unfortunately, these bare facts have no impact upon motivation. We need to look closer.

The story is not about them. It is about us: what kind of people are we?

The current full-blown genocide is a grotesque escalation of a pattern of mass murder and ethnic cleansing that has been ongoing since the birth in blood and terrorism of the settler colonial state of Israel in 1948. My own awakening to the realities of Palestine came at the end of 2008. During the 2008/9 Gaza massacre, a defenceless and trapped civilian population were under attack. Residential apartment blocks were being obliterated by missiles. In Zaytoun, forty people were herded into a single house. 21 of them died when the Israeli occupation army then shelled the house.  Ambulances, also targeted, were denied access, and wounded children were left for days in the rubble beside their dead relatives. The dehumanisation, the sadistic cruelty, the suffering and the terror, and the sheer sickening scale of it was in itself almost a life-changing experience. Then came the words of one young mother whose terrified children could not sleep. An Al Jazeera reporter, Sharine Tadros, looking for the ‘human story’ was asking how she was managing. Despite her calm, serene demeanour, the young woman’s feeling of helplessness was palpable, not knowing if she or her children would still be alive the next day. At one point, she turned to the reporter and asked, ‘how can the world stand by and let this happen?’ In that instant, it is personal. This is no longer a televised story about the plight of some Arabs in the Middle East. Her words cut through the illusion of disconnection. “How can the world stand by and let this happen?” With these words, it hits home, viscerally. The story is not about them. It is about us: what kind of people are we?

Ambulances, also targeted, were denied access, and wounded children were left for days in the rubble beside their dead relatives. The dehumanisation, the sadistic cruelty, the suffering and the terror, and the sheer sickening scale of it was in itself almost a life-changing experience. Then came the words of one young mother whose terrified children could not sleep. An Al Jazeera reporter, Sharine Tadros, looking for the ‘human story’ was asking how she was managing. Despite her calm, serene demeanour, the young woman’s feeling of helplessness was palpable, not knowing if she or her children would still be alive the next day. At one point, she turned to the reporter and asked, ‘how can the world stand by and let this happen?’ In that instant, it is personal. This is no longer a televised story about the plight of some Arabs in the Middle East. Her words cut through the illusion of disconnection. “How can the world stand by and let this happen?” With these words, it hits home, viscerally. The story is not about them. It is about us: what kind of people are we?

A sociologist might ask why some people are out demonstrating, and some, like Palestine Action — now shockingly proscribed as a ‘terrorist’ organisation — risking jail sentences for civil disobedience, while ‘normal’ people are at home watching TV. The DNA of the activist and the couch potato are indistinguishable. The activist, however, has been exposed at some point to the human story. That is what fuels their commitment to the welfare of these ‘others’. When we see a young mother who loves her children, who is living in the middle of a war zone — a surreal, settler-colonial war of elimination, with an army on one side and civilians on the other — and when it sinks in that she has been robbed of any reason to believe that her beloved children will survive the night, the fiction evaporates, and in its place comes a cold anger, a commitment, a solidarity rooted in the reality that her humanity and mine are one and the same. When she asked how we can stand by and let this happen, I believe that she asked possibly the most important question that science has the power to answer. And yet this pathology of culture that separates the British people from the victims of British capitalism and neo-colonialism — their fellow human beings in Palestine — is not so complex as to defy analysis.

it is not the elites who determine the behaviour of nations but the location of the mean of a frequency distribution

Let us, for the moment, assume that the theory is sound, that extreme egoism and altruism are the verifiable extremes of the baseline motivational spectrum. A simple statistical mind experiment now confronts us with the vision of a population distribution approaching normality, with egoistic Trump and his like at one tail, most of the population piled up near the middle, and altruistic Mandela at the other tail. If that is the case in the real world – and answering that question is the purpose of the research I’ve been arguing for – then an extraordinary perspective emerges from the bizarre world of statistics and probability.

Firstly, it is clearly impossible to be more than 100% committed to one’s own welfare or to that of others. No-one can be more than 100% egoistic or altruistic, and most of us must fall between these two extremes. Altruism-egoism, if it exists at all, is a spectrum. If we admit that the distribution of such a spectrum in any society is likely to approach normality, then that finite distribution must follow the laws of probability. Even a slight shift in the distribution in either direction will exponentially affect the tails where the proportions of highly motivated individuals – the highly egoistic or highly altruistic – are inversely related.

With respect to the laws of probability, this proposition is uncontroversial. It leads to a deeply counter-intuitive conclusion: that it is not the elites who determine the behaviour of nations but the location of the mean of a frequency distribution. A population that tends to be slightly more egoistic than altruistic will tend disproportionately to produce and to be led by a proliferation of egoistic personalities, career politicians serving corporate interests. As Hannah Arendt noted of Eichmann, “Except for an extraordinary diligence in looking out for his personal advancement, he had no motives at all.”

Should this proposition strike you as preposterous, I can only agree wholeheartedly that it seems so, but if, as I believe, such a spectrum does exist in the real world, if altruism and narcissism are qualities more or less normally distributed throughout society, then that is the inescapable statistical reality of our culture, the cause and the consequence of the pathology of an individualistic, capitalist, consumer society. It has often been said that the weak are led by the weakest. The theory following merely explains the mechanism.

To Bauman’s ‘collateral casualties’ of consumerism must be added that the ‘invisible hand’ of the market has shifted my imaginary curve in the wrong direction. Relentless marketing and social media manipulation to idealize celebrity lifestyles and thus maximise desire for goods and services may have normalised the habit of a seemingly innocuous but statistically consequential degree of egoism, while diminishing the value of community. Meanwhile, there are still millions of altruistic-leaning individuals in every walk of life, but especially since Reagan and Thatcher, the idea of the selfish gene is never far from the zeitgeist, just as in its day, the self-justifying appeal of social Darwinism was seized upon and disseminated by racist European elites profiting from the plunder and exploitation of the so-called ‘uncivilised world’.

Meaningful change requires societies that insist upon it. Science has been misused since the days of Empire to justify the cults of nationalism and individualism, but it also has the potential to expose the pathologies of capitalism, neo-imperialism and militarism as being not only afflictions but also products of our own societies, our own marginally egoistic cultures. The first hurdle, therefore, if these arguments are reasonable, is to create testable hypotheses based upon the theory following that, as I have said, proposes a model for the mechanism of baseline motivation which, if valid, leads us to conclude that egoistic motivation is a thoroughly natural and healthy motivational state, in the infant personality.

Psychologists sometimes speak of the normal personality as distinct from the dysfunctional personality, but in a society of cannibals, ‘normal’ is far from desirable. A slightly egoistical culture is a pathological culture, a dangerously pathological culture, and in a Western consumer society, the normal personality is a motivationally immature personality enjoying a level of adult altruistic motivation far, far below the potential within every individual. The attributes that Trump has made so familiar are consistent with a pronounced arrested development of the system of baseline motivation as described in the theory that follows here. It is tempting to believe it possible that that understanding alone might help reverse the cultural shift that Reagan and Thatcher effected, and perhaps ultimately help reverse the trajectory that I believe we have been on since Europeans first started trading in tea, sugar, tobacco, and black people.

[end of expanded section]The biology of narcissism and the case for research

I am a man and that means I am a combination of two very different animals: I am at once the father of my son, and the child of my parents. One of these two will have been in charge for most of the day.

Baseline motivation can be the most defining quality of personality, the most enfeebling or the most empowering. An example might be in the energised behaviour of the parent bird feeding her chicks, where a consistently high baseline level of global motivation modulates each instance of instrumental motivation involved in the task of leaving the nest, finding food and returning — a demanding business repeated throughout most of the day with undiminished vigour. In contrast, abnormally low levels of baseline motivation are typically associated with chronic depression.

In the laboratory, manipulation of approach/avoidance motivation necessarily assumes goal-directed motivation over the time window of the experiment. However, this requires a level of baseline motivation independent of the instrumental motivation under study, and persisting over an extended timeframe.

Research at the biological level has proposed tonic dopamine release as being implicated in coding for baseline motivation. However, the persistence of the common-sense assumption of motivation being necessarily goal-directed has contributed to precluding a conceptualisation of the mechanism of baseline motivation, thus eliminating an avenue of research into a non-trivial factor in human behaviour. Whereas instrumental motivation is indeed goal directed, I will argue that the same is not the case for baseline motivation, that it can be either cause or goal-driven, that the primitive mechanism of baseline motivation is distinct from the ‘reward circuit’, and that it comprises rather a corticothalamic dopaminergic system coding for a variable representing the urgency of action.

the central concept: the conflict of active and passive baseline motivation in the normal personality

The word ‘motivation’ currently carries the implicit but misleading assumption that it refers, necessarily, to something that drives our own behaviour – we might say that an athlete’s success was due to her motivation. However, that is to overlook a crucial component of the mechanism: directionality. I am equally capable of being motivated to elicit or influence the behaviour of others for my benefit. That is to say motivation can be either active or passive. The distinction deserves close attention. This concept of a mechanism for ‘passive motivation’ is central to the model. The theory proposes the co-existence in the normal personality of both active and passive motivation, and proposes also that passive motivation (i.e., motivation to elicit or influence the behaviour of others) serves a distinct neurological function, having its roots in the infant personality.

At the most basic level, we might consider baseline motivation to be subserving homeostasis: the need to find food, shelter and to be alert to danger. Unlike the adult which is capable of serving these needs by its own action, the infant’s motivation references not its own action but the action of the carer. Orthodox accounts of infant motivation gloss over this behaviour, explaining that the infant merely blurs the distinction between the internal and external world. However, this model rests upon the proposition that the ‘passive’ system modulating motivation to elicit the action of the carer is necessarily distinct from that of the mature personality where baseline motivation drives the individual’s own behaviour: the healthy adult baseline system situates the individual as the subject, the originator of action, whereas the infant personality is situated as the object, the recipient or beneficiary of the actions of its carers.

The model rejects the assumption, valid in the case of instrumental motivation, that the degree of baseline motivation is simply a matter of its intensity. It proposes that baseline motivation is a neurological variable derived from the processing of the urgency of action. It further proposes the co-existence of passive and active urgency (baseline motivation) in the normal personality as a mechanism having a direct bearing upon the individual’s propensity for narcissistic and manipulative behaviour.

In speaking of ‘passive urgency’, the meaning here is literal, no more than that. As reflected in English grammar, the nature of action is two-fold:

Active: the police push the activists back

Passive: the activists are pushed back by the police

Passive motivation is a commonplace phenomenon such that, on one level, it is a matter of putting a name to something with which we are all familiar. Put at its simplest, passive urgency works to elicit or influence, for your benefit, someone else’s perceptions and behaviour. For example, it might be expressed in the pursuit of status, wealth or social capital, or less effectively, in bragging, seeking to impress in conversation or by the acquisition of status symbols, or some might ingratiate themselves with a superior at work. You might be thinking that we all do some of these things. Actually, no, we don’t. Passively motivated behaviour may be commonplace, but outside of childhood and early adulthood, it is far from being universal. It is a matter of managing or manipulating the perceptions and behaviour of others, but it is also a matter of degree. Abusive, manipulative relationships, though complex in their psychological origins, are manifestations of passive urgency. We tend to focus on the details – the gaslighting, guilt-tripping, deception, transference of blame etc. – and yet a common thread lies in the underlying motivation to influence or control the behaviour of the victim for the benefit of the manipulator.

It might be tempting to argue that manipulating others is simply another way of achieving one’s goals, but this suggestion fails in the parsimony it strives for; it attributes a degree of sophistication to the infant personality that would be quite inexplicable.

The central question is this: am I invariably the subject in my motivation or might I sometimes be the object, the intended recipient and beneficiary of someone else’s action? Is my motivation, at this moment, active, or do I, with this behaviour, really just intend to promote the odds of agreeable things happening to me? The significance of this question lies in the proposition that some largely grow out of the habit of passively motivated behaviour while others do not. It is not only dimensional; it is developmental.

For those who would prefer to follow the chronology of an idea as it developed, the hidden section below on ‘intellect type’ sets out the ideas that led eventually to the main theory, i.e., the conflict of active and passive baseline motivation in the normal personality. It also adds a layer of complexity that only muddies the waters at this stage. In brief, I believe it can be shown that, with respect to baseline motivation, two intellect types – root intellect and branch intellect – are evident. The past-oriented, root intellect type tends to interpret events and motives in terms of their causes, while the future-oriented branch intellect tends to rationalise these events in terms of their intended goal. That, I think, is enough said for the moment. The theory has its origins in but is not wholly premised upon this typology and I think, at least for some, it is best introduced without this de facto layer of potential confusion. [word count ~ 2220]

intellect type

I believe it can be shown that, in the context of motivation, two intellect types – root intellect and branch intellect – are evident.

To introduce the basis for proposing this intellect typology, we can take a fresh look at a belief that passed for science back in the days of Freud and Jung. It is interesting to see how we got here and how easily a crucial insight that could have informed research can be overlooked or forgotten because of poor terminology.

Freud & Co. often argued about their patients and how to interpret their symptoms. Hidden in plain sight in the preface to ‘Psychological Types’ (Vol. VI in the Collected Works), is arguably one of the most insightful elements of Jung’s entire commentary on the subject. It is here that he recounts the observation that gave rise to his theory of Extraversion and Introversion: it was one of those disagreements. Freud and Adler were arguing about a patient whose ‘hysteria’ Freud attributed to events in her past, but Adler was sticking to his guns: yes, of course, she has some repressed memories, but Freud was completely missing the point: what was really going on here was that she had discovered a way of getting power over her husband. Jung was watching this interminable debate going nowhere, but what he was thinking about was the argument itself.

Jung’s original concept of Past/Future Intellect Orientation

Jung had become aware of something that he found intriguing, and it stemmed from his realisation that Freud and Adler might be imposing their own personality type upon the patient. The entirety of Freud’s argument referenced events in the patient’s past. Everything Adler countered with related to her aim to achieve something in the future. Jung’s first thought was that he seemed to be looking at some kind of past/future intellectual orientation, a tendency that neither Freud nor Adler seemed able to shake off.

He found the idea so compelling that he tasked himself with the search for an explanation. Jung hypothesized what he called ‘object fixation’ as an explanation for Freud’s apparent preoccupation with past causes and origins. He dismissed the possibility of Freud’s evident intellectual past-orientation being perhaps some kind of strongly reinforced trait or even an innate intellectual tendency. By proceeding to question what lay behind the phenomenon I believe Jung made an error in logic, mistaking the principle for the derivative. This, nevertheless, was the foundation for his now well-known theory of extraversion and introversion.

The early psychologists were, of course, working almost completely in the dark. Some of their beliefs were, to be blunt, simply nonsense, and few more so than the notion of psychic energy. Jung’s ‘extraversion and introversion’ were the terms he coined to describe the direction – outward or inward – of this flow of ‘psychic energy’. While his terms have survived in differential psychology, their original meaning is now altogether lost, and for the rather persuasive reason that psychic energy has long since been proven not to exist.

It is sometimes argued that the idea of psychic energy was no more than a working metaphor, but that doesn’t really hold up; they believed in its existence. In physics, the theory of the conservation of energy had been transformative, and the early psychologists felt they needed something of that nature to help put their work on a scientific footing. Some individuals clearly had immense resources of ‘energy’, throwing themselves vigorously and tirelessly into their work whereas some others were inexplicably lethargic. The obvious answer, psychic energy, was borrowed from physics, and the convenience of it proved tragic for the infant science, not just because it was wrong but because, I hope to show, it was so nearly right.

Most interestingly, libido – generally taken to mean sexual drive – and psychic energy were sometimes used synonymously, and so while the idea of extraversion or introversion of the libido made sense to Jung, Freud’s writing of that period presents libido as a well of psychic energy and having no ‘inward’ or ‘outward’ component. Toward the end of his life, Freud came to view libido as being a bi-directional affair, but his new model was still radically different from Jung’s: Freud latterly promoted the idea of a positive-negative conflict: a life drive and a death drive.

- The Jungian theory of libido gave us two personality types: the extravert (outward-flowing libido) and the introvert (inward-flowing) – neither one any ‘better’ than the other – just different – one tending to be more outgoing, the other more reserved.

- Late Freudian libido theory introduced a much more serious proposition: a positive and a negative flow of ‘energy’ – one life-giving, creative, and the other a drive for death and destruction, echoes of God and the Devil.

The Jungian and Freudian theories of libido appeared, therefore, destined to remain utterly incompatible, and ultimately, seemingly irrelevant to science.

So, why waste time on this? We know that psychic energy does not exist so what could possibly be interesting about a disagreement regarding its mechanics? The problem, I hope to show, lay not so much in the impossibility of justifying their beliefs but in the limitations of the concepts then available to them. In particular, they had no access to the neuroscience concept of a variable. I’ll return to this, but for the moment, let me continue the thread of Jung’s past/future intellect orientation.

motivation of the ‘terrorist’

(Apologies for writing in the first person. I’ll try to be brief).

A long time ago, I got into an argument about the IRA and the violence in Belfast. In the course of that argument, an extraordinary thing happened: I caught a look which told me that the other man thought he was talking to a complete fool.

His (Adlerian – goal-focused) argument centred on the imagined ambitions of the Catholic minority. Given the chance, he insisted, they would do everything they could to disempower and drive out the Protestant majority in the North of Ireland. On the other (Freudian – cause-fixated) side, I found it hard to get past the history. I saw Republican resistance as a natural consequence of the cruelty and injustice of British colonial rule. I was listening to this man adduce fact after fact to prove the anti-Protestant intent of the Catholic minority and then I catch a look that tells me that he thinks I don’t have what it takes to follow his argument. The irony astonished me!

What, at essence, we were discussing were the motives behind the then-ongoing ‘terrorist’ attacks. But, sparked by that look, what was now focussing my attention was not the argument itself but a sense of an underlying difference in our fundamental approach to the subject: the consistency with which I had been presenting a past-related explanation for the actions of the IRA and a consistency in the counter-argument presenting a future-related attribution of what they wanted to achieve, their aim to disempower and expel. And that was what he thought I was failing to understand. Each time that he put forward his (technically) reasonable argument regarding the aims and ambitions of the Catholic minority, I had failed to address it in the terms in which it was presented. He mistakenly believed I wasn’t understanding what he had to say, but I had been making exactly the same mistake, and presenting historical fact and context as if that alone was all that mattered.

This was not a five-minute argument and yet the consistency was 100%. Increasingly, I came to suspect that this was more than just an argument from polarized positions on the armed struggle; it was more and more like an argument between two completely incompatible types of intellect.

What it came down to, on my part, was an instinctive tendency to assume motivation ultimately to be explicable not in terms of its goal but in terms of its origin, its cause. I saw the motivation of ‘the terrorist’ as a product of his experience and of the injustice that he had seen, first-hand, inflicted upon his community. My feeling was that his motivation – his commitment to the cause – arose, in large measure, from his empathy with his community, the oppressed victims of the British and the loyalists. But this cause-oriented attribution has no resonance for someone for whom the aim or goal of every action is instinctively proposed as an explanation: the terrorist, consumed by an irrational hatred of the established order, is intent on spreading suffering, death and destruction. Bear in mind that the question at this stage relates to my own intellectual tendency, as distinct from an academic framing of behaviour in terms of cognition and motive.

Some years later, I read Carl Jung’s ‘Psychological Types’ and his account, in the preface, of that argument in which Freud seemed to understand behaviour only in terms of its cause while Adler seemed able only to frame it in terms of the goal. I would have, as I imagine many others have done, passed over Jung’s account of the backstory of his extravert/introvert theory without any genuine depth of interest had it not been for my own experience. In the event, I knew exactly what he was talking about; I was primed to give it credence and found myself concurring with his apparent conviction that this communication problem was telling us something about how the brain processes information relative to motivation. Unlike Jung, however, I had, at that time, neither the wish nor the wit to look deeper. I simply and naively accepted, to my own satisfaction, the likelihood, particularly with respect to motivation, of there being two intellect types: past and future oriented.

Freud’s intellect (and intellectual aptitude) was, by Jung’s account, fundamentally past-oriented (which might be termed root-intellect) while Adler was, equally unmistakably, future-oriented (branch-intellect). The utility of this proposition will, I hope, become clear.

(Please feel free to ignore this paragraph. I first wrote it forty years ago and I don’t have the talent to fix it but some folk may be able to thole it).

I mentioned earlier that I believe Jung made an error in logic. I think it is worth noting that Jung’s ‘subject/object’ concept of introvert and extrovert differentiation discussed perception rather than action, i.e. the subject is aware of the object and attributes a certain relative value or importance to it. But the concept of extroversion is, of course, meaningless without reference to what he termed the libido, and the concept of the libido (or baseline motivation) assumes that the relationship between subject and object is not inert. If the ‘libido’ is object-directed, it cannot be a matter of mere awareness. The relationship must have reference to the potential, either active or passive, of action, in the widest sense. Perception, in this context, is, I believe, relevant to the psyche only in as much as it is prerequisite to action. The possibility, potential, or intention of action of the subject upon the object or of object upon subject (which might be termed passive potential) is, I think, what is of concern to both types, the ‘root-intellect’ type requiring, at the most fundamental level (i.e., programmatically), to conceptualize action in terms of cause, the ‘branch-intellect,’ in terms of its goal. The apparent importance which the two types attach to either subject or object is, if that is the case, a consequence of the two interpretations of that which is the principal concern of the psyche: the potential actions and events which either actively or passively relate subject and object. That is to say, the observed intellectual orientation is, in fact, the reason for the extrovert/introvert differentiation which Jung hypothesised to explain it.

Root Intellect and Branch Intellect

The premised past-oriented intellect is typified by the tendency and aptitude to get to the root of the issue. It will always tend to focus upon cause. Where there is a need to understand, it is in terms of the radical. Does the mind tend to the radical; does it focus upon the root of the issue; is the aptitude root and cause related? These tendencies and aptitudes are suggestive of the past-oriented intellect – the root intellect. It follows also that, for the root intellect, a high score for root/cause aptitude should be accompanied by a low score for branch/goal aptitude.

The less-common future-oriented branch intellect is typified by the tendency and aptitude to extrapolate and to deal with the goals, aims, consequences and ramifications of the issue. There is frequently a marked tendency to be observant, to absorb, without effort, a proliferation of detail. That facility has, I suspect, cascaded from the distinct core ability and tendency to extrapolate, to consider the consequences of an event, the ramifications. For the branch intellect, actions are instinctively rationalised in terms of their goals.

The part that this differentiation plays will become apparent although the model I’m about to set out is not premised upon it. If anything, it is the existence of this differentiation that has helped muddy the waters, with both the immature introvert personality of the passively motivated root-intellect and the healthy mature introvert personality of the actively motivated branch-intellect being erroneously conflated.

Intellect Type

| Orientation | Type | Focus | Aptitude |

| Past | Root Intellect | source; cause: origin | Convergent: to reduce to the fundamentals, the radical |

| Future | Branch Intellect | goals; aims; consequences | Divergent: to extrapolate; to see ramifications |

the age of narcissism and entitlement

Why does a baby cry? It is, of course, because it is incapable of satisfying its needs by its own action. It has an instinctive and subsequently-reinforced sense of entitlement to have its needs satisfied by the action of the carer: “feed me – comfort me – reassure me of my security.” This is passive motivation in its purest and most natural form, but thirty years later, that same degree of narcissism, manipulation and entitlement persisting in the adult personality would be considered pathological.

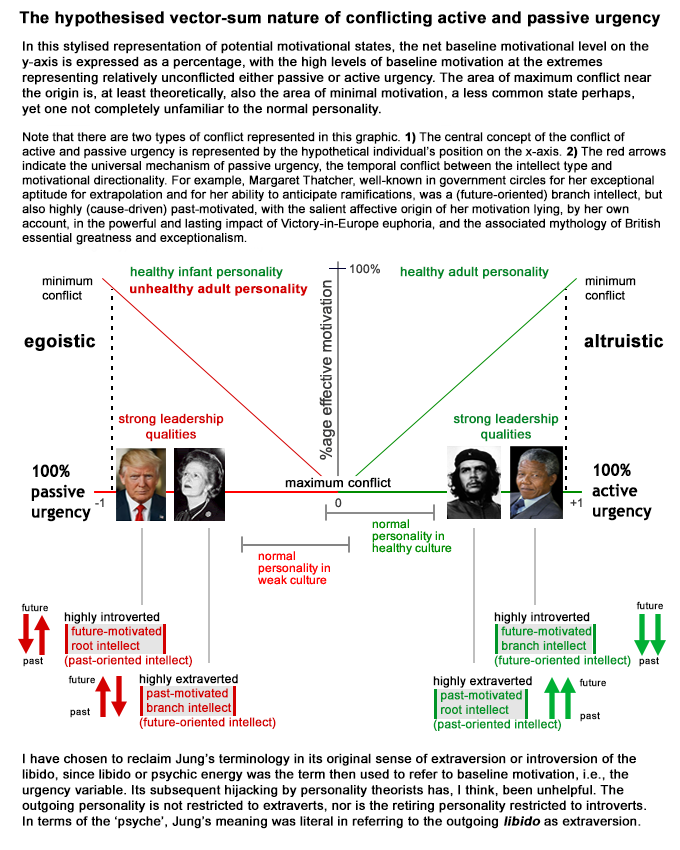

If the model is valid, however, the system mediating passive motivation does persist in the adult personality – the active and passive systems co-exist. Baseline motivation is hypothesised to be not simply a matter of gain or intensity, but the net output of these two conflicting systems.

The obvious question as to why I should propose two coexisting systems of motivation when one might seem to suffice to explain behaviour was almost answered many years ago by Abraham Maslow when he stressed the importance of research focusing upon what he termed the self-actualising personality. When we restrict research to the study of the normal personality, the typically low levels of baseline motivation that we can infer might seem to suggest that baseline motivation has a minimal impact upon behaviour. This is true only of the normal personality. The motivational conflict of the normal personality renders motivation levels comparatively weak and indistinct. Analagous to inverse wave cancellation, it is an enfeebling, vector-like conflict ensuring that, for the normal personality, the immense motivational potential of the individual is never remotely reached or even imagined. However, the key to unlocking that potential is both simple and accessible: it is commitment.

the empowerment of commitment

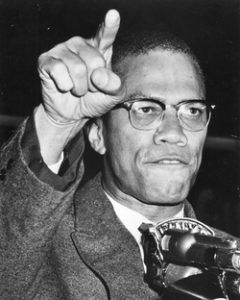

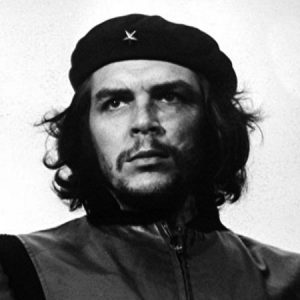

We intuitively venerate some individuals, not just for their talent or their intellects but for their actions and their level of drive and focus, their commitment to serving needs external to their own. An abnormal degree of active baseline motivation is the distinguishing feature of exceptional personalities like Nelson Mandela, Leila Khaled, Malcolm X, Fanny Lou Hamer, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King and Che Guevara, aptly described by Franz Fanon as “the world symbol of the possibilities of one man”. Rather than probe the confusion of the conflicted, relatively weak and thus relatively obscure baseline motivation of the normal personality, we should look, firstly, at those individuals – Maslow’s self-actualising personalities – whose abnormally high levels of active and correspondingly low levels of passive motivation place them at the far reaches of the normal distribution.

It is almost a redundant statement but it is the degree of personal commitment to the cause or goal that determines the level of baseline motivation, the outcome, in the rare case of complete commitment, being virtually unconflicted motivation, an exceptional level of drive, focus and consciousness. The significant difference between Mandela and the rest of humanity was, of course, his complete commitment to the cause: “I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people… It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

That degree of commitment is sufficiently rare as to lie entirely outside of the experience of most psychologists (Maslow being the obvious exception). This is important since it is recognition of the absence of motivational conflict characterising the completely-committed personality that points to the dimensional nature of the active/passive motivational spectrum and to the enfeebling nature of the highly-conflicted baseline motivation of the normal personality in the infantilizing milieu of an individualistic Western consumer culture.

In contrast to those highly motivated altruistic personalities, we can also consider their opposites: the highly motivated narcissists. Donald Trump is an exemplar. At every turn, Donald Trump betrays a disturbingly unremarkable intellect. It is his motivation, his focused self-obsession and his relentless egoistic drive that mark him out as head and shoulders above all those around him. His entire history speaks of a degree of manipulative egoistic motivation that is mercifully extremely rare. His lack of conflicting motivation could hardly be more obvious. That is his ‘strength’. He is unreservedly and ruthlessly committed to the welfare of Donald Trump – a paragon of a fully-grown adult with the passive, manipulative motivational vector of an infant. He gets what he wants because he will do what it takes to make the deal, where a healthier individual would balk at the injustice or the suffering that might follow.

And like an infant, he is almost devoid of empathy. Any measure of empathic motivation is, for the highly narcissistic personality, seen as weakness. And this is a thoroughly valid assessment on their part: their ‘strength’ lies in their lack of exactly such conflicting motivation. Judging always by their own standards, their Hobbesian view of the state of nature, red in tooth and claw — “a war of all against all” — is no place for bleeding heart liberals.

romantic love: a transformative and empowering motivational state of relatively unconflicted active baseline motivation

I have been discussing the motivation of exceptional figures whose dedication to a cause or goal derives generally from powerfully affective personal experience, often involving witnessing great suffering or injustice. Che Guevara’s motorcycle journeys introduced him to the widespread poverty and suffering that transformed a young medical student, product of a comfortable middle-class family, into a committed revolutionary and an international icon of resistance who will inspire for generations to come. But I have said that altruism is a universal and ubiquitous driver of human behaviour. A much more familiar form of altruistic commitment is romantic love. The theory affords an alternative framing of romantic love as being a highly empowering baseline motivational state, an instinctively triggered active baseline motivation simply and literally to care for and be committed to the welfare of the other person. However much affection we might feel for them, we love our children to the extent that we are committed to their welfare. This is, I believe, the very essence and origin of the systems of active and passive baseline motivation. Put another way, love is the word we use to refer to the far from rare phenomenon of relatively unconflicted active baseline motivation.

As a pair-bonding species with offspring that are slow to mature, we evolved the capacity to love because survival required that we are committed to caring for each other and for our children. The tendency is to discuss (and even research)! love from an experiential perspective or in terms of attachment, but much more pertinent and explanatory is the radical motivational transformation at which point the infantile, passive, self-focused vector is effectively reversed, giving way to a personal commitment to the welfare of the other person. Naturally, we romanticise it, but love, as distinct from the most visceral lust and the deepest affection, can be defined as a transformative baseline motivational state arising from an instinctive personal commitment to the welfare of another person, and anyone who has been in love has tasted the empowering and life-changing phenomenon of relatively unconflicted active baseline motivation.

You may ask why, if that is the case, is society not replete with profoundly empowered, actively motivated individuals? The answer has to be two-fold. Firstly, and especially in a Western consumer culture, we can always regress, revert over time to our earlier infantile self-focused motivational state. Secondly, the question assumes that most people fall in love, but that may be far from the reality. We learn to love by being loved as children, and for the many who have limited experience of the unqualified love of a parent, likewise, their own capacity to love is liable to be limited to some degree. Paradoxical as it may seem, love and desire are two very different things, potentially complementary, but almost opposites on a deeper level.

Survival of the family and of the community places certain obligations upon its members. The healthy parent is intuitively aware that the needs of the family must take precedence over the desires of the individual. Weakness, however, breeds weakness. The unhealthy parent tends to impede motivational development in the child by placing insufficient emphasis upon encouraging empathy and considerate, unselfish behaviour both by instruction and, more importantly, by example. The selfishness of the individual in one situation emerges as an equivalent weakness or inadequacy in another. The exception proves the rule, but the child which is exposed to the extreme selfishness of its parents might be expected to follow in their footsteps, and perhaps eventually treat us to the joys of his so-called ‘narcissistic personality disorder’. Depending on the depth of his pain, he may achieve some local notoriety as a sociopath. As long as we fail to recognize the simplicity – the direct relationship between selfishness and motivational immaturity – we lack sufficient understanding to tackle the underlying societal sickness at source.

baseline motivation: a variable

Assuming the existence of active and passive baseline motivation, the challenge is to make sense of it as a neurological mechanism. It is recognised that tonic dopamine release can modulate the gain of instrumental motivation, but the underlying cognitive systems regulating baseline extracellular dopamine levels in the infant and adult personalities remain to be elucidated. However, it seems likely that we are discussing a mechanism that has evolved over millennia, suggesting that the key to understanding baseline motivation as a biological function may lie in the evolution of ‘action’ itself, and we already know more than enough about that to trace its development with some confidence, even if armed with no more than a nebulous notion of the evolution of some imaginary creature at the dawn of the Cambrian explosion.

Apologies if the following comes across as a series of just-so stories. I think it is worth taking the time to move through and beyond the traditional accounts of primitive life in order, hopefully, to demonstrate that there is almost an element of inevitability in the evolution of motivation and consciousness.

evolution of locomotion

In early prey/predator interactions, we might consider locomotion as a stimulus response to, for example, shadow or to olfactory cues indicating the proximity of a predator. However, while survival will tend to favour the creature that has evolved that threat response, it is still a grossly inefficient behaviour: it means bursts of release of unattenuated energy and yet, of course, at this level of existence, conservation of energy is everything.

motion detection and time

A subsequent stage might see the emergence of response to perception of movement, perhaps something akin to radial motion opponency (looming detection). This in itself would represent a significant qualitative change. However, a seismic shift in survival advantage would occur when that response was ultimately superseded by processing of the rate of expansion of the stimulus as detected on the retina. This novel information – still a stimulus-response – is highly adaptive in that it translates ultimately to an evaluation not of the spatial proximity of the predator but of the temporal imminence of the attack. And we know it happened: it is a capability common to almost all vertebrates.

The arms-race nature of prey/predator evolution leads inexorably to selection pressure not only for spatial proximity and motion-detection responses but ultimately for the supreme efficiency of persistent monitoring both of attack-imminence and of competing survival imperatives. This, however, involves a completely novel type of perception and processing. In order to provide an input that can evaluate to attack imminence, perception has to be processed over time. And that is what is most salient about this processing: the calculation involves the ongoing processing of a data-stream of perception against time. But this represents a massive leap forward in survival advantage. It is the temporal imminence of the threat, rather than its spatial proximity, that has now become the dominant survival-critical issue: a predator nearby calls for elevated alertness; a predator closing in at speed represents imminent danger.

evolution of the urgency variable

The game-changing significance of this processing of perception over time is that, because it is evaluating the temporal imminence of the threat, the creature is now triggering escape contingent upon the urgency of action. The prototype of baseline motivation has effectively come into being in the form of a data-stream-derived variable: urgency. There may be no trace of it in the fossil record but this facility to initiate and regulate locomotion in response to the urgency of action can only have conferred a major step change in survival advantage both in terms of escape outcomes and in terms of conservation of energy.

The data-stream-based urgency variable is also the optimum moderator of the energy released to locomotion. Not too far down the line, we are discussing a creature (an ancestor) that can conserve energy and life by modifying its own speed and direction in a pursuit context in response to a data-stream-based assessment of a dynamic threat. Locomotion is initiated and regulated according to an ongoing assessment of the imminence of the threat and therefore the varying urgency of action. This is a highly complex sequence of data-stream-based calculations and of note should be the fact that we are now discussing a plausible ancestor of consciousness, one having a definition not far removed from the more concise of modern attempts: the ongoing processing of time and perception to initiate and moderate action.

[As a first stab at testing, I believe agent-based modelling would demonstrate that urgency-enabled agents would significantly out-perform proximity-sensitive agents.]

In short, I believe I am on reasonably solid ground in proposing that the progenitor of animal motivation and consciousness was this facility to calculate and be continually responsive to the varying urgency of action. The probability, throughout our subsequent evolution, of the persistence (in consciousness) of that single variable, urgency, continually and globally moderating effort and awareness, is far from being an untenable inference. I say ‘in consciousness’ but I believe it may be the core mechanism of consciousness. The processing of time is absent only in syncope, anaesthesia and (possibly) coma.

Human motivation, the urge to act, is sometimes described subjectively as having an ‘intensity’ but, programmatically, neurologically, it is, I submit, the ongoing calculation of the urgency of action that globally modulates motivation and effort. The ancient Chinese philosophers spoke of positive and negative ‘Chi’. Jung and Freud called it libido or psychic energy. Bowlby called it nonsense.

baseline motivation – the candidate neural substrates

So, where in the brain should we expect to find the system coding for an urgency variable? Much of the research into motivation at the biological level investigates instrumental approach/avoidance motivation. It is more difficult to find work that sheds light on the system coding for baseline motivation, and I’m afraid the following effort at homing in on candidate anatomy is liable to undergo revision; it represents my current understanding. (Like an infant learning to speak, hopefully the babbling stage will pass).

If the evolutionary tale is feasible, it points to a primitive structure capable of initiating and modulating action in response to crude visual signalling, thus probably implicating the superior colliculus (looming-selectivity). The model also suggests that manipulation of extrinsic urgency may result in modulation of signalling detectable (EEG) in multiple cortical regions. However, correlating with a state of elevated urgency, an increase in activation (fMRI) might be expected at an evolutionarily-feasible locus where there is early access to the visual datastream and where a plausible mechanism exists for its processing against time. I suspect that such a characterisation may point to a dopaminergic system that involves the thalamus. [Of the 2024 review paper linked here, I understood perhaps 5%, but enough, nevertheless, to suspect it provides some support for what was previously no more than a hunch, based, as I have said, on the thalamus’s early access to the visual stream together with the potential of oscillatory thalamocortical neurons for encoding urgency, i.e., the processing of the visual stream against time.]

The thalamus has traditionally been viewed as a ‘hub’ or relay station. It has also been proposed as the mediator of ‘temporal coherence‘ (Llinás, Ribary, Contreras and Pedroarena, 1998) thus, according to the researchers, providing a plausible basis for coherent consciousness. However, it seems not unreasonable to speculate that its function may include its coding for urgency, regulation of baseline motivation. The hypothesised processing of urgency requires a system capable of an ongoing evaluation of a datastream of perception against time. The thalamus is anatomically and functionally well-placed to process perception and time: the oscillatory activity of thalamocortical neurons provide one of several plausible mechanisms for short-scale time measurement, and of course, both the visual and auditory datastreams are routed through the thalamus. Interestingly, the one system that does not seem to pass through the ‘hub’ is the olfactory system, and if you recall my just-so story of the evolution of the variable, it is only the visual and auditory data streams that can carry the information necessary to facilitate encoding of temporal imminence. The olfactory signal synapses instead on the olfactory bulb and goes straight to the amygdala, hippocampus and hypothalamus where it can trigger the more primitive spatial-proximity-based threat response.

Another potentially interesting area of research is the thalamic role of the neuromodulator dopamine. Research has traditionally focused on the role of phasic dopamine in predictive-error learning, i.e., in reward-directed behaviour with, for example, drugs that block dopamine receptors reducing an animal’s motivation to engage in reward-generating behaviour. Regulation of instrumental motivation is a component of the reward system but, even within the confines of the behaviourist paradigm which still informs so many research methodologies, dopamine has also been shown to be a component of aversive behaviour. A 1998 paper (Berridge and Robinson) posits the role of dopamine in some contexts as a component of the reward system but modulating motivational value “in a manner separable from hedonia and reward learning”. They employ the term ‘incentive salience’ and this, if not quite a synonym, is a much better fit for the potential role of a corticothalamic dopaminergic system in coding for the urgency of action.

Both the Freudian and Jungian concepts of libido were based upon the recognition of the ubiquitous phenomena associated with urgency. The early psychologists, however, and naturally enough, described it as ‘psychic energy’ and that mistake, combined with the discovery of a more apt metaphor for mental activity in the static logic circuits of early electronic control systems, was enough to lead others subsequently to discard Freud’s and Jung’s psychodynamic theories as worthless.

Freud had speculated counter-intuitively that a drive to death and destruction (‘Thanatos’) is an element of the normal personality and he saw that drive as being unaccountably in conflict with a healthy drive to life (‘Eros’). I believe the time-based construct of the urgency variable reveals the mechanism, and in this regard, the crucial aspect of the human psyche is that we are born helpless. The infant human, dog, bird or elephant instinctively expects to be cared for. Instinctively, it rightly assumes that it is entitled to have its needs satisfied by the actions of those around it. The role of urgency is revealing, therefore, because the infant’s urgency is of a very special nature in that it does not reference its own action; it is manipulative, referencing the action of the carer.

the conflict of active and passive urgency in the normal personality

Identifying the passive nature of infant motivation is, I believe, key to understanding adult narcissism and the mechanics of baseline motivation in the adult personality. If the model is valid, there coexists, in the normal personality, a silent conflict of active and passive urgency subsequently expressed cognitively in motive and choice. What’s going to happen to me? What will I get out of this? What do people think of me? The logic of these considerations might seem beyond question, but the reality is that while for one individual, “what will I get out of this?” might be the first consideration, for another, in just the same circumstance, it might be the last. The theory of the conflict of active and passive urgency rejects the behaviourist and frankly schoolboy-like assumption of the universality of self-gratifying motives.

the cognitive basis of empathy

The model frames empathy as a survival-critical cognitive facility of parenthood, the facility to ‘feel’ some representation of the infant’s urgency. It is, at least in part, because of the (healthy) parent’s capacity for empathic motivation that the infant’s communication of its own egoistic urgency can trigger, on the part of the parent, an appropriate measure of motivation to attend to the infant’s needs. Parenthood is, I believe, the root psychological basis of empathy, compassion and altruism.

narcissism and the egoism-altruism spectrum

narcissism and the egoism-altruism spectrum

The infant’s de facto lack of responsibility, its characteristic narcissism, its lack of empathy, its instinctive and valid sense of entitlement, and its passively motivated manipulative behaviour are all natural, healthy and essential for survival. It is only unhealthy and detrimental to society when these characteristics persist and prevail in adulthood.

The theory proposes that:

- the data-stream-derived urgency variable lies at the core of the neurological mechanisms of baseline motivation and consciousness

- consciousness, in its minimal form, can be defined as: the ongoing processing of time, perception and introception to initiate and regulate action

- the normal personality lies on an egoism-altruism spectrum: urgency can sustain simultaneously both a passive and an active component

- and the reason being that life has two-stages: childhood and parenthood.

I mentioned earlier that the section on intellect type (root intellect and branch intellect) adds a layer of potential confusion, albeit a de facto layer. I imagine that the graphic below, which illustrates the vector-sum model, can only tend to increase scepticism over what must already be an unattractive theory. However, for those who managed to persevere through the section on intellect type, some explanation of the hypothesized relationship between intellect type and baseline motivation is due.

Note that the proposed ‘highly introverted’ motivational state (Trump and Thatcher) employs Jung’s original terminology (direction of libido ‘flow’) rather than the familiar re-assigned meaning of modern personality theorists who, I imagine, would classify his personality as clearly extravert. They are not wrong. It is just unfortunate that Jung’s libido-focused terminology was appropriated to this entirely different domain.

On re-reading the above text on Thatcher, I am reminded to suggest a likely association between the affinity for the notion of national exceptionalism that characterises both Trump and Thatcher, and the ego-centrism, the ‘personal exceptionalism’, of the motivationally immature personality in general. Perhaps a bit tenuous, but the nationalistic sentiment of Trump’s MAGA base — elevating the importance of one’s own country — is anathema to the motivationally mature (i.e., altruistic) personality, as is the racism that frequently accompanies these nationalistic fantasies. Both Trump and Thatcher (and Hitler come to that) were concerned with and identified with nationalist fantasies – the imagined ‘greatness’ of their nations – whereas both Mandela and Guevara were focused on injustice, as being the lived experience of their people, i.e., they were motivated by their compassion, and by reality, as experienced by real people.

I think I can now repeat the statement made in the introduction and, hopefully, it now carries more meaning:

I am a man and that means I am a combination of two very different animals: I am at once the father of my son, and the child of my parents. One of these two will have been in charge for most of the day.

Through whose eyes do I see the world? With whose mind do I understand – the child or the man? I keep coming back in my mind to the Israel-Palestine ‘conflict’ (a disgustingly inappropriate term for indigenous resistance to settler colonialism, ethnic cleansing, dehumanisation, decades of full-spectrum brutality, sadistic military occupation, oppression, land expropriation, water and resource expropriation, sporadic tantrum-like frenzies of mass murder, and a level of apartheid that shocked Tutu and Mandela). In July 2014, Israel was once again inflicting a murderous collective punishment of grotesquely disproportionate force upon the Palestinians they have imprisoned and besieged in the Gaza strip – over 2,100 dead – babies to grandparents – two thousand one hundred human beings, extinguished – calculated physical and psychological trauma on a scale utterly unimaginable. The message was simple: “fear us; we are very powerful, and we will act without restraint; Hamas has brought this upon you.”

Since October 2023, the entire world has watched, stunned, shocked, almost to the point of denial of the reality before us as a genocide unfolded in plain sight, the numbers long since bereft of any comprehensible meaning. Sixty thousand murders in the space of twenty months. Sixty thousand dehumanised victims of a racist culture of hate that the vast majority of the British people are completely unaware of, and yet it has been in existence for decades.

With whose mind do the architects of this carnage understand – the child or the man? Freud recognised the death drive as an ubiquitous but unaccountable phenomenon. It is anything but unaccountable if the theory is sound: the construct frames cruel, destructive, unempathetic behaviour, denial of responsibility and transference of blame, in terms of the persistence, in the adult personality, of the predominance of infantile passive, egoistic motivation.

Narcissism is not just about the criminal of the tabloids; it is about the real world: the human cost of the evils of capitalism, imperialism, militarism, settler-colonialism, elitism and racism. It is about the intense, incalculable suffering of millions of the most vulnerable at the hands of men, and occasionally women, whose arrested motivational development grants them license to behave manipulatively, ruthlessly and without compassion or remorse, as would any infant.

I will conclude by reposting the image of Hind Rajab and the ambulance whose crew who were murdered as they tried to save her life. Hind’s story, for me, is emblamatic of the sickness of the Israeli society that produced her murderers. Hind was not a casualty of war. She and countless others like her, were murdered in cold blood. In Hind’s case, we have the harrowing, unforgettable audio record. But she was not, as you might imagine, murdered by a psychopathic member of the Israeli Occupation Force. To the murderer of this beautiful six-year-old girl, she, like all Palestinian children, was vermin. Her murder can be laid at the door of the normalised dehumanisation of Palestinians that has been incubated in Israeli society. At least equally to blame are the Western politicians who have granted impunity to Israel for decades, and to this day continue to supply the weapons to murder Palestinian children. The impunity that the murderer of Hind Rajab relied upon as he fired 335 rounds into the car in which Hind was to be the last survivor — the other family members in the car died hours before Hind — is endemic in the Israeli Occupation Force. It derives from the impunity enjoyed by the state of Israel itself, courtesy of Downing Street and Washington.

However, if the preceding theory is sound, the pathology of British culture that produced our self-serving, criminal political class can be traced to the mean of a frequency distribution, a consequence of Western capitalist consumer culture and its desperately misplaced values.

And having said that, I now realise that the preceding sentence will make no sense whatsover since I cleverly hid the section that sets out the significance of the hypothesised egoism/altruism spectrum. Apologies to those who opted to read through that section, but I think this is important. I now have to repost the graphic and at least some part of the explanatory text. The following is an excerpt from that section. It was introduced with the following pull-quote: “it is not the elites who determine the behaviour of nations but the location of the mean of a frequency distribution”.

Altruism-egoism, if it exists at all, is a spectrum. If we admit that the distribution of such a spectrum in any society is likely to approach normality, then that finite distribution (+/- 100%) must follow the laws of probability. Even a slight shift in the distribution in either direction will exponentially affect the tails where the proportions of highly motivated individuals – the highly egoistic or highly altruistic – are inversely related.

With respect to the laws of probability, this proposition is uncontroversial. It leads to a deeply counter-intuitive conclusion: that it is not the elites who determine the behaviour of nations but the location of the mean of a frequency distribution. A population that tends to be slightly more egoistic than altruistic will tend disproportionately to produce and to be led by a proliferation of egoistic personalities, career politicians serving corporate interests. As Hannah Arendt noted of Eichmann, “Except for an extraordinary diligence in looking out for his personal advancement, he had no motives at all.”

The central thesis of my research must focus upon the individual, but the by-product of the theory is by far the more important proposition: nations, like individuals, can be healthy or they can be sick. And it is not always possible to determine which by examining their internal organs. One has to look also at their behaviour.

All engaged in genocide studies will agree that genocide is invariably preceded by dehumanisation. German society of the 1930s first dehumanised Jews. Their subsequent industrial slaughter was no crime in the minds of their murderers. In the Nazi psyche, the Jews were vermin. We have Israeli leaders on video speaking in that same language. They are so blind to their own sickness of mind that they do not even try to hide it. It is for all the world as if the psychic disease that was Nazi Germany merely found a hew host in this settler-colonial European outpost in West Asia, a state that embraced ethno-supremacism, racism, militarism, expansionism and capitalism as national virtues. However, those ultimately responsible for the genocide are much closer to home.

As I said previously, I have no reputation to lose. I feel no need to conceal my anger, my contempt for our career politicians, or my conviction that this is a disease that science has the power to eradicate.